444 After November 4

- Curators' Team

- 24 hours ago

- 4 min read

The Time It Took to Reshape US-Iran Relations After the Attack on the US Embassy

On November 4, 1979, Iranian students stormed the American embassy in Tehran, initiating a crisis that went beyond the dramatic international standoff itself. The Iran Hostage Crisis became a turning point in global diplomacy, reshaping foreign policy paradigms and deeply influencing public perceptions in both countries.

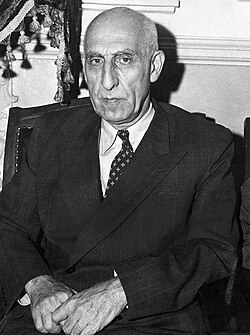

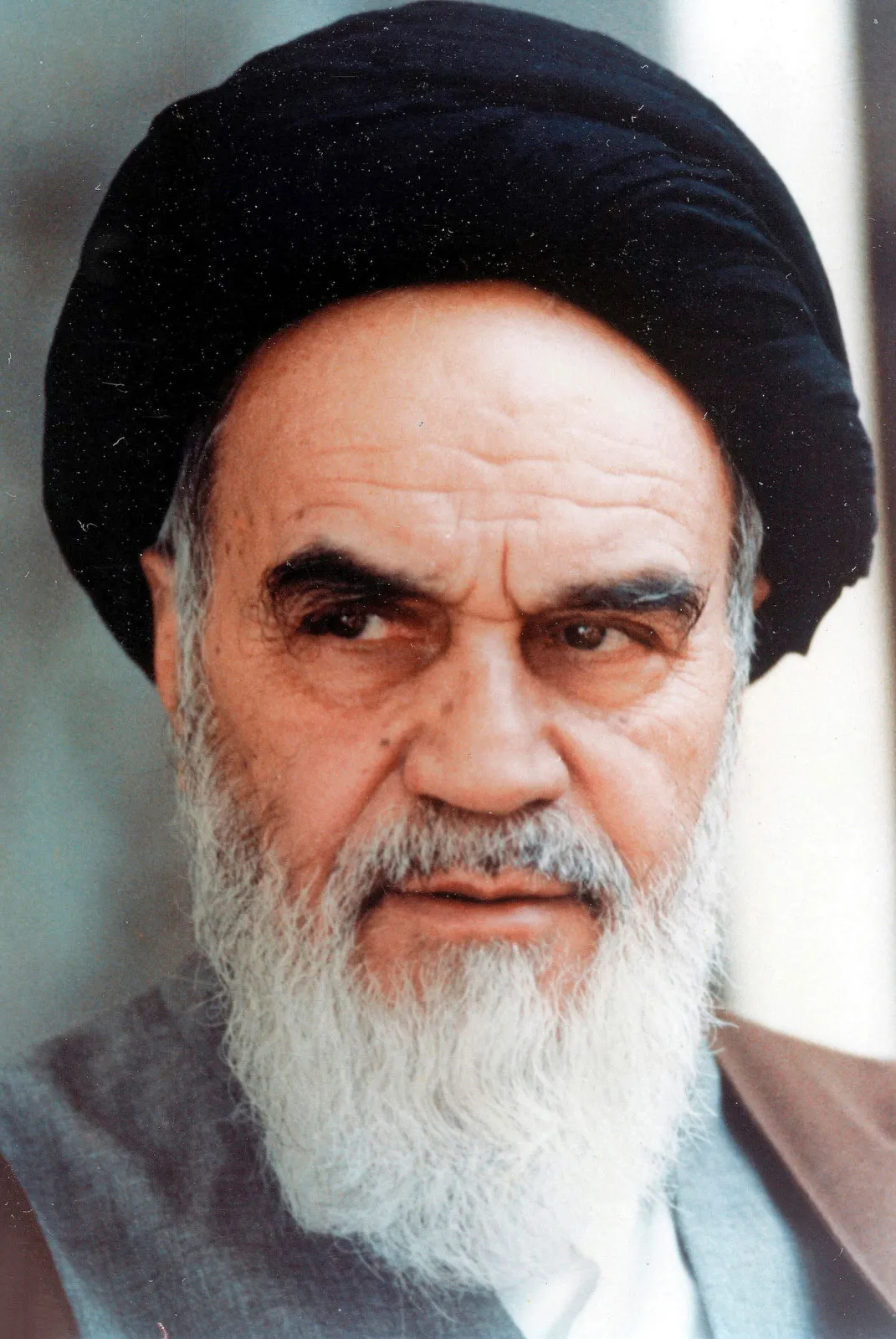

The origins of the crisis can be traced back to the 1953 coup orchestrated by the CIA and British intelligence, which removed Iran’s democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, and restored Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Though the Shah launched modernization programs, his autocratic rule and human rights abuses fueled resentment. By the late 1970s, opposition coalesced into the Iranian Revolution, which overthrew the Shah and established the Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The memory of foreign interference and the trauma of the coup created deep suspicion of the United States, setting the stage for the embassy takeover.

Mossadegh, the Shah, and Khomeini—three figures who shaped modern Iran

The Seizure and Its Motives

The immediate catalyst was the United States' admission of the exiled Shah for medical treatment. Iranian protesters, viewing the American embassy as a symbol of U.S. interference, took 66 Americans hostage. The students, backed by the new revolutionary government, framed the act as both a form of resistance to imperialism and a means of solidifying revolutionary ideals and power. The crisis thus served as both a tool for domestic consolidation of the revolution and an international statement against foreign domination.

President Carter and the failed Operation Eagle Claw

For 444 days, the hostages endured deprivation and psychological stress as the world watched through continuous media coverage. The crisis fueled anti-American sentiment in Iran and became a rallying point for revolutionary fervor. In the United States, it sparked outrage and political unrest, dominating headlines and shaping the 1980 presidential election. President Jimmy Carter’s administration faced mounting pressure as diplomatic efforts stalled, and a daring rescue mission, Operation Eagle Claw, ended in tragedy. The failure highlighted operational limitations and contributed to Carter’s electoral defeat, paving the way for Ronald Reagan’s rise.

Diplomacy, Negotiations, and The Resolution

The path to resolution was marked by intricate diplomatic negotiations, with Algeria acting as an intermediary. The hostages were finally released on January 20, 1981, minutes after Reagan’s inauguration, following the Algiers Accords. Because Iran refused direct talks with the United States, Algerian diplomats relayed messages between the two sides throughout late 1980. Iranian leaders demanded the unfreezing of assets, guarantees of non-interference, and a mechanism to resolve financial disputes. These negotiations, lead by U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher and Algerian Foreign Minister Mohamed Seddik Benyahia culminated in the Algiers Accords, which established an escrow system for Iranian funds and created an international tribunal to handle claims between the two countries. The resolution involved concessions, such as the unfreezing of Iranian assets, and underscored the complexities of high-stakes diplomacy.

The aftermath of the crisis saw the United States sever diplomatic ties with Iran, impose sanctions, and adopt a more cautious approach to the Middle East. In Iran, the crisis consolidated the revolutionary government’s power and entrenched its anti-Western stance. It also set a precedent for enduring mistrust between the two countries, shaping their bilateral relations for decades.

Media coverage on both sides fueled competing national narratives—American broadcasts emphasized the hostages’ suffering, while Iranian media framed the crisis as a victory for sovereignty and resistance. These portrayals highlighted the power of the media in shaping public opinion and national identity. On a broader scale, the Iran Hostage Crisis provided lasting lessons in crisis management, diplomacy, and the unpredictable nature of international relations. It underscored the need for strategic adaptability, patient negotiation, and cultural understanding in the conduct of foreign policy.

Argo F*** Yourself

Cultural portrayals in film and literature have continued to explore the Iran Hostage Crisis, shaping public memory and deepening reflection on its political and human dimensions. Over the decades, books, memoirs, and films have examined the causes of the crisis, the experiences of the hostages, and the broader consequences for U.S.–Iran relations. Many of these works focus on themes of diplomacy, secrecy, media influence, and Cold War–era geopolitics, helping audiences understand the complexity of the events beyond the headlines.

One film that stands out is the Oscar-winning Argo (2012), directed by and starring Ben Affleck. The movie dramatizes the real CIA operation to extract six American diplomats who escaped the U.S. embassy takeover and hid in the Canadian ambassador’s residence. Disguised as a fake Hollywood science-fiction production, the operation—known as the “Canadian Caper”—used deception and international cooperation to safely evacuate the diplomats from Iran.

Argo received widespread acclaim and won the Academy Award for "Best Picture," bringing renewed public attention to the Iran Hostage Crisis. While the film has been praised for its tension and storytelling, historians have noted that it simplifies certain aspects of the crisis and minimizes the role of Canadian officials in favor of dramatic effect. Nevertheless, its trailer and promotional materials emphasize suspense, covert intelligence work, and the high stakes of diplomacy, reinforcing how popular media can influence public understanding of historical events.